“I neither know, nor think that I know.” –Socrates

According to historical legend, this is the response Socrates gave when the Oracle of Delphi asked why he was considered the wisest person of his time.

Plato, the student of Socrates, recorded this story in his famed Apology.

The brilliance of this statement lives on into the modern era.

The answer that Socrates gave is an important professional posture to hold, and perhaps just as vital for our personal lives.

A current example

I currently help lead a fairly large team of people who perform similar tasks.

As with any large group, we have a range of abilities.

But we have frequently found that the most experienced people are not the most skilled.

And the problem we encounter is that often these are also some of our most confident people.

How could that be?

Because real expertise is not about logging more hours—it’s about your commitment to consistent improvement.

We have some newer team members that practice this with rigorous discipline, thus becoming true experts more rapidly.

This process is painful for the ego, because if you are constantly learning or looking at what you could do better, you don’t get to “feel” like a true master. It also takes more energy for your brain to keep learning. Your brain would much rather slip into the cognitive ease of doing the same task the same way over and over again without changing it.

Furthermore, our brain is a prediction machine that enjoys having a clear model for how we approach life or perform our daily tasks, so our mind is likely to hold tightly to old theories or outdated frameworks—even in light of updated, and especially, contradictory—information—even if that information is true.

If you want to become an authentic expert, you will have to work against these natural tendencies of your mind.

The best scenario is when one can log years of experience combined with a commitment to ongoing improvement. These people truly soar to the top of their field.

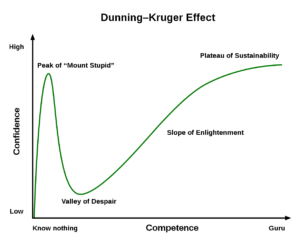

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

In 1999, social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger published an interesting study entitled, Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.

They found that “much incorrect self-assessment of competence derives from the person’s ignorance of a given activity’s standards of performance.” They further said, “without the self-awareness of metacognition, people cannot objectively evaluate their level of competence.”

The researchers found that people with low skill sometimes have high, and erroneous confidence, because it doesn’t match their actual level of ability.

See diagram below for illustration.

I recently interviewed a former Navy Seal on our podcast who shared part of their training philosophy called “realistic self-appraisal.”

He explained that the reason Navy Seals often exude such incredible authentic confidence is because they have been put through a scrupulous and repeated process of self-examination and constant feedback—so they know exactly where they stand when compared to the current highest standards.

After all, you do not want to be second-guessing your training or true skill level when the battle starts.

It’s easy to think you are an expert when you are not aware of how skilled others may be, or evolving standards in any field.

Are you ready to change your mindset, set your ego aside, and make a commitment to being a real expert in an important area of your life?

You will find the journey difficult, but worthwhile.

Take action now

- Radically accept your brains desire for certainty and routine. This is an essential first step. You must begin observing your natural habits of mind in order to overcome them. Build self-awareness.

- Make a habit of asking for feedback. It’s a fact that most humans fear conflict and are afraid to give feedback, which means you really have to ask for it and convince the other person you can handle it. Then you have to remind them you truly want it. Observe your psychological defenses kick in when they start providing you with feedback.

- Find out the current best practices for your field. Nearly every field has standards. Whatever you want improve, be it skiing, soccer, chess, or your profession—find the current “best practices” or people practicing at a high level. Start by learning from them and then continue to build.

- Talk to people with opposing views. My good friend Eric is amazing at this. He makes a regular habit of staying in touch with people who hold very different political, religious, or professional views than his own. Shoot, I never even know when he is disagreeing with me because of his brilliant and curious approach. It may not be healthy to talk to people who really inflame you. Start with those who differ slightly.

- Stay open, stay curious. Curiosity is the antidote to judgment. You don’t have to give an opinion on everything. Commit to curiosity. Ask better questions. Listen. There is great freedom in this posture.

- Consider this when hiring. It drives me crazy when people talk about hiring “the people with the most experience” because often is not the best predictor of who will be a rockstar team member. By all means, look for people with enough experience to meet your standard, but then rigorously search out the real superstars who have a demonstrated mindset for ongoing learning, less ego, and high self-awareness. Hiring for experience only runs the risk of building a team of people who are egotistical, lacking in self-awareness, and don’t take feedback well. Hiring even one person like this can suck your time and kill morale fast.

Have a great weekend!

Parker

*If you have enjoyed Parker’s blog, check out The Next Peak Podcast that Parker co-hosts. We interview successful leaders and discuss research-based principles that help people win in the workplace without compromising the things that matter most—relationships, a life of purpose, and health.

Want more? Suggested Resources Below

- The Dunning-Kruger Effect explained